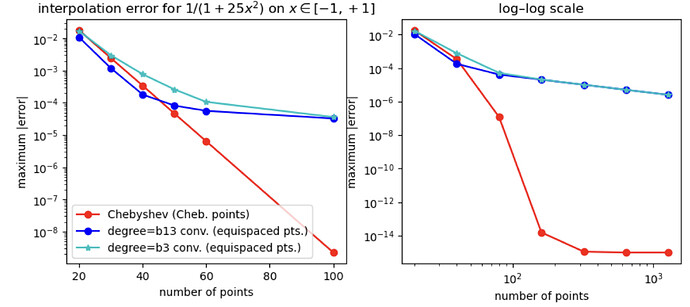

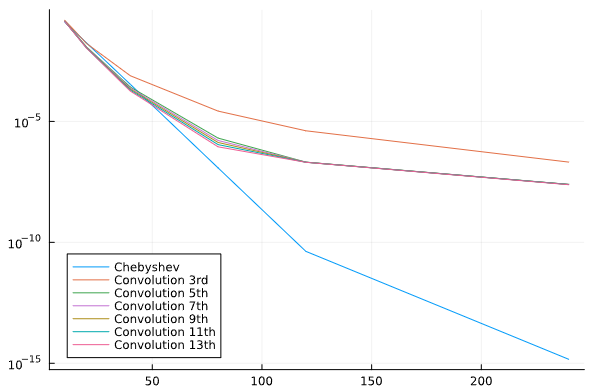

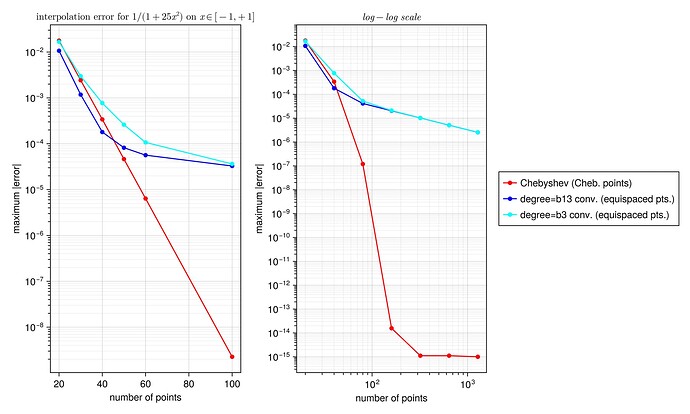

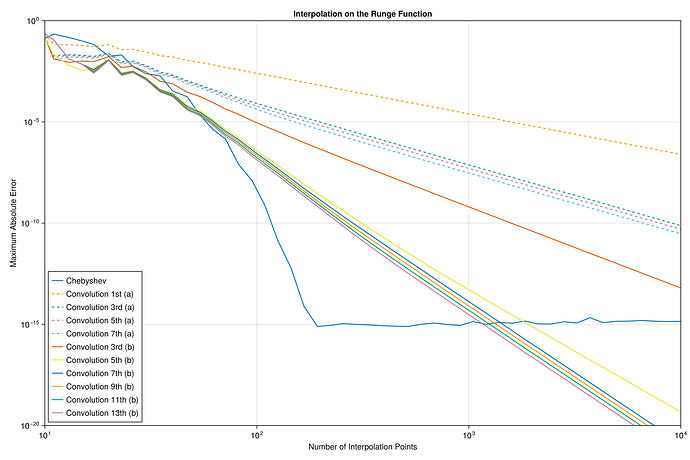

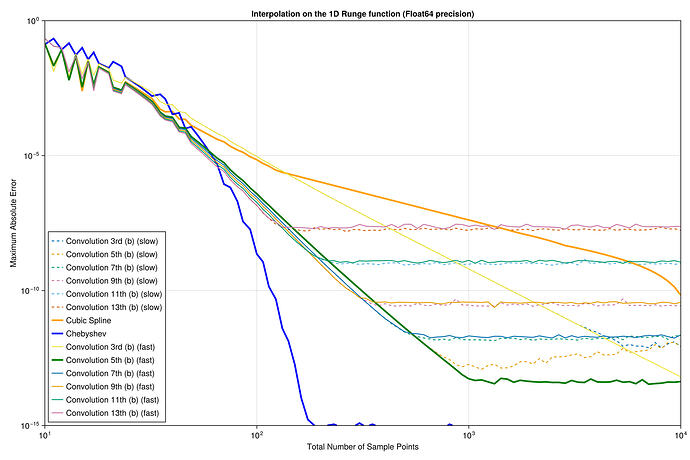

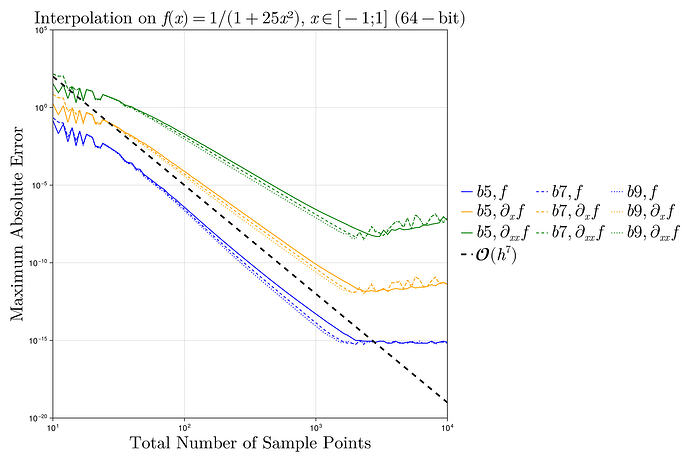

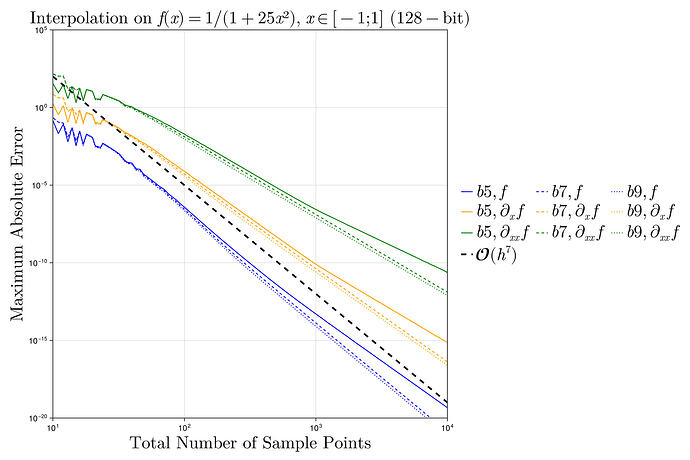

I did a quick test with these interpolants on the Runge test function 1/(1+25x^2) on x \in [-1,1], looking at the maximum error maximum(abs.(interp.(x) .- exact.(x))) at 10^5 equispaced points x = range(-1, 1, length=10^5), plotting the convergence as a function of the number of interpolation points.

I found something strange to me: if I compare your degree-13 kernel :b13 to the degree-3 kernel :b3, the former is more accurate at first, but asymptotically they have the same accuracy. Why doesn’t the high-order kernel converge faster?

Am I missing something?

For comparison, I’ve also included the FastChebInterp.jl polynomial interpolation using the same number of Chebyshev points, which converges exponentially with the number of points. Of course, there are lots of circumstances where you are forced to use equispaced points and cannot use Chebyshev points!

Code

using ConvolutionInterpolations, FastChebInterp

runge(x) = inv(1+25x^2)

xf = range(-1, 1, length=100000)

yf = runge.(xf)

ns = [20,30,40,50,60,100]

errs = [

begin

xc = chebpoints(n, -1,1)

c = chebinterp(runge.(xc), -1,1)

xr = range(-1,1, length=n)

itp3 = convolution_interpolation(xr, runge.(xr); degree=:b3);

itp13 = convolution_interpolation(xr, runge.(xr); degree=:b13);

maximum(@. abs(c(xf) - yf)), maximum(@. abs(itp3(xf) - yf)), maximum(@. abs(itp13(xf) - yf))

end for n in ns

]

nslog = [20,40,80,160,320,640,1280]

errslog = [

begin

xc = chebpoints(n, -1,1)

c = chebinterp(runge.(xc), -1,1)

xr = range(-1,1, length=n)

itp3 = convolution_interpolation(xr, runge.(xr); degree=:b3);

itp13 = convolution_interpolation(xr, runge.(xr); degree=:b13);

maximum(@. abs(c(xf) - yf)), maximum(@. abs(itp3(xf) - yf)), maximum(@. abs(itp13(xf) - yf))

end for n in nslog

]

using PyPlot

figure(figsize=(10,4))

subplot(1,2,1)

semilogy(ns, getindex.(errs, 1), "ro-")

semilogy(ns, getindex.(errs, 3), "bo-")

semilogy(ns, getindex.(errs, 2), "c*-")

xlabel("number of points")

ylabel("maximum |error|")

legend(["Chebyshev (Cheb. points)", "degree=b13 conv. (equispaced pts.)", "degree=b3 conv. (equispaced pts.)"])

title(L"interpolation error for $1/(1+25x^2)$ on $x \in [-1,+1]$")

subplot(1,2,2)

loglog(nslog, getindex.(errslog, 1), "ro-")

loglog(nslog, getindex.(errslog, 3), "bo-")

loglog(nslog, getindex.(errslog, 2), "c*-")

xlabel("number of points")

#ylabel("maximum |error|")

#legend(["Chebyshev (Cheb. points)", "degree=b13 conv. (equispaced points)", "degree=b3 conv. (equispaced points)"])

title("log–log scale")