I was reading this article about OCaml’s special int type:

The tl;dr is that OCaml represents data as a 64-bit header followed by the actual data. This includes int64 and, often, floats. However, they special case the default int type so that the least significant bit is always set to true. This allows them to check that value is an int, not a pointer.

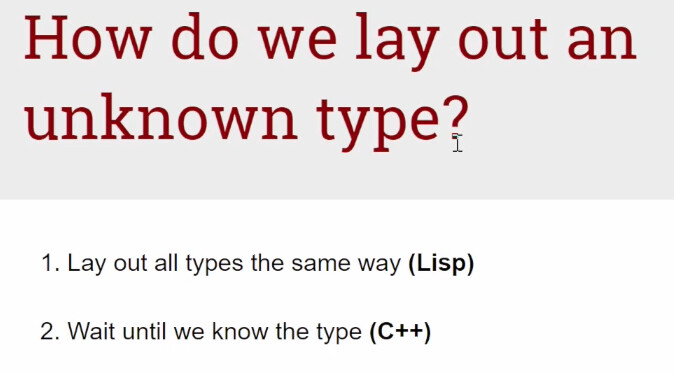

As a compiled language with a rich type system, I’m shocked that there isn’t enough information for the complier to elide tags and unbox almost everything. However, I don’t know any OCaml folks, so I thought I’d try the inverse question here:

Why doesn’t julia need to box isbits types in most cases?

Edit: Some additional context from another article:

a float value is represented by a pointer to a block (tag 253) holding one data word (64-bit) or two (32-bit). Floats are thus boxed, and a single float value requires three or four words (one for representing the pointer, one for the block header, and one or two for the float bits). Note that this representation is only required when floats are stored in data structures, or passed from one function to another. Within a single function’s body, local float values can be represented unboxed in memory or in registers, and the OCaml compiler apply such optimisations. There are also plans to allow unboxed calling conventions between functions.

About unboxed float arrays | LexiFi

So local floats are stored on the stack, but if you have a field in a record, then it’s actually a pointer to a heap allocated float (unless all the fields are floats).