Hello,

I want to model a vector stochastic process (may be decided according to historical observations).

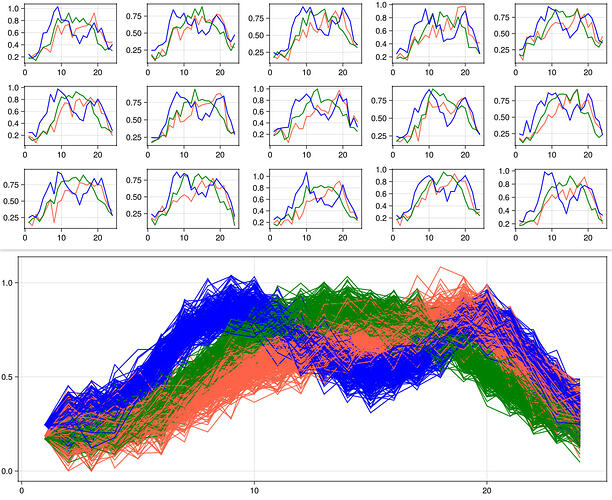

The length of the vector is N, which is the number of wind farms spreading in a power transmission network.

There are 24 hours in a day, denoted by T = 24.

I want to take account of temporal and spatial correlations.

A sample of the entire stochastic process should be a N-by-T matrix of wind power. Maybe the wind power of farm n at time t can be normalized to be in the interval [0, 1].

My minimum requirement about the uncertainty model is:

- I need the conditional distribution of column t+1 given the realization of column t (in the matrix above). (Yes, (I assume) it has Markov property)

My question is:

- Are there any advisable methods to build such an model realistically? (e.g. do I have to “transform” the numerics somehow (e.g. logistic function, z-score…)?)

Some additional notes:

My knowledge on statistics/regression/time series forecast is limited. And my knowledge on (engineering) wind power modeling is also zero.

I know there is a AR(1) model:

where \mu is a vector and \Phi is a matrix, both are weights to be decided on. And \epsilon_t is a stagewise independent error process (with multivariate normal distributions).

Since the \mu and \Phi do not depend on t, I naturally have a question here:

- Can I build 23 separate (vector) linear regression models? (the first one models the transition from t=1 to t=2, the second one models the transition from t=2 to t = 3…) Suppose I have enough historical data. So I can decide the weights separately for each transition with the respective data. Will this be feasible? What’s the difference compared with a naive AR(1) model?

And finally I want to ask:

- Are there any related mature julia packages in this regard?