For another angle on this (and in case I can interest anyone in some proofreading), I’ve drafted the relevant changes to the documentation.

The draft

Note: this will look a bit funny because it hasn’t been processed by Documenter. Hence the @ref/@id links, and example blocks that are supposed to be executed to produce the output content shown in the docs.

[StyledStrings](@id stdlib-styledstrings)

CurrentModule = StyledStrings

DocTestSetup = quote

using StyledStrings

end

!!! note

The API for StyledStrings and AnnotatedStrings is considered experimental and is subject to change between

Julia versions.

[Styling](@id stdlib-styledstrings-styling)

When working with strings, formatting and styling often appear as a secondary

concern.

For instance, when printing to a terminal you might want to sprinkle ANSI

escape

sequences

in the output, when outputting HTML styling constructs (<span style="...">,

etc.) serve a similar purpose, and so on. It is possible to simply insert the

raw styling constructs into the string next to the content itself, but it

quickly becomes apparent that this is not well suited for anything but the most

basic use cases. Not all terminals support the same ANSI codes, the styling

constructs need to be painstakingly removed when calculating the width of

already-styled content, and that’s before you even get into handling multiple

output formats.

Instead of leaving this headache to be widely experienced downstream, it is

tackled head-on by the introduction of a special string type

([AnnotatedString](@ref Base.AnnotatedString)). This string type wraps any other

AbstractString type and allows for formatting information to be applied to regions (e.g.

characters 1 through to 7 are bold and red).

Regions of a string are styled by applying [Face](@ref StyledStrings.Face)s

(think “typeface”) to them — a structure that holds styling information. As a

convenience, faces can be named (e.g. shadow) and then referenced instead of

giving the [Face](@ref StyledStrings.Face) directly.

Along with these capabilities, we also provide a convenient way for constructing

[AnnotatedString](@ref Base.AnnotatedString)s, detailed in [Styled String

Literals](@ref stdlib-styledstring-literals).

using StyledStrings

styled"{yellow:hello} {blue:there}"

[Annotated Strings](@id man-annotated-strings)

It is sometimes useful to be able to hold metadata relating to regions of a

string. A [AnnotatedString](@ref Base.AnnotatedString) wraps another string and

allows for regions of it to be annotated with labelled values (:label => value).

All generic string operations are applied to the underlying string. However,

when possible, styling information is preserved. This means you can manipulate a

[AnnotatedString](@ref Base.AnnotatedString) —taking substrings, padding them,

concatenating them with other strings— and the metadata annotations will “come

along for the ride”.

This string type is fundamental to the [StyledStrings stdlib](@ref

stdlib-styledstrings), which uses :face-labelled annotations to hold styling

information, but arbitrary textual metadata can also be held with the string,

such as part of speech labels.

When concatenating a [AnnotatedString](@ref Base.AnnotatedString), take care

to use [annotatedstring](@ref StyledStrings.annotatedstring) instead of

string if you want to keep the string annotations. The annotations of

a [AnnotatedString](@ref Base.AnnotatedString) can be accessed and modified

via the [annotations](@ref StyledStrings.annotations) and [annotate!](@ref

StyledStrings.annotate!) functions.

julia> str = AnnotatedString("hello there", [(1:5, :pos, :interjection), (7:11, :pos, :pronoun)])

"hello there"

julia> lpad(str, 14)

" hello there"

julia> typeof(lpad(str, 7))

AnnotatedString{String, Symbol}

julia> str2 = AnnotatedString(" julia", [(2:6, :pos, :noun)])

" julia"

julia> str3 = Base.annotatedstring(str, str2)

"hello there julia"

julia> Base.annotations(str3)

3-element Vector{@NamedTuple{region::UnitRange{Int64}, label::Symbol, value::Symbol}}:

(region = 1:5, label = :pos, value = :interjection)

(region = 7:11, label = :pos, value = :pronoun)

(region = 13:17, label = :pos, value = :noun)

julia> str1 * str2 == str3 # *-concatenation works

true

Note that here the AnnotatedString type parameters depend on both the string

being wrapped, as well as the type of the annotation values.

!!! compat “Julia 1.14”

The use of a type parameter for annotation values was introduced with Julia 1.14.

[Faces](@id stdlib-styledstrings-faces)

Styles are specified through the Face type, which is designed to represent a common set of useful typeface attributes across multiple mediums (e.g. Terminals, HTML renderers, and LaTeX/Typst). Suites of faces can be defined in packages, conveniently referenced by name, reused in other packages, and [customised by users](@ref stdlib-styledstrings-face-toml).

The Face type

A [Face](@ref StyledStrings.Face) specifies details of a typeface that text can be set in. It

covers a set of basic attributes that generalize well across different formats,

namely:

fontheightweightslantforegroundbackgroundunderlinestrikethroughinverseinherit

For details on the particular forms these attributes take, see the

[Face](@ref StyledStrings.Face) docstring. However, it is worth drawing

particular attention to inherit, as it allows us to inherit attributes from other

[Face](@ref StyledStrings.Face)s.

The attributes that specify color (foreground, background, and optionally underline) may either specify a 24-bit RGB colour (e.g. #4063d8) or name another face whose foreground colour is used. In this way a set of named colors can be created by defining faces with foreground colors.

!!! compat “Julia 1.14”

Direct use of Faces as colors was introduced with Julia 1.14.

juliablue = Face(foreground = 0x4063d8) # Hex-style colour

juliapurple = Face(foreground = (r = 0x95, g = 0x58, b = 0xb2)) # RGB tuple

Face(foreground = juliablue, underline = juliapurple)

Notice that the foreground and underline color are labelled as “unregistered”.

While assigning Faces to variables is fine for one-off use, it is often more

useful to create named faces that you can reuse, and other packages can build on.

[Named faces and face""](@id stdlib-styledstrings-named-faces)

StyledStrings comes with 32 named faces. The default face fully specifies all

attributes, and represents the expected “default state” of displayed text. The

foreground and background faces give the default foreground and background

of the default face. For convenience, the faces bold, light, italic,

underline, strikethrough, and inverse are defined to save the trouble of

frequently creating Faces just to set the relevant attribute.

We then have 16 faces for the 8 standard terminal colors, and their bright

variants: black, red, green, yellow, blue, magenta, cyan, white,

bright_black/grey/gray, bright_red, bright_green, bright_blue,

bright_magenta, bright_cyan, and bright_white. These Faces, together

with foreground and background are special in that they are their own

foreground. This is unique to these 18 faces, as their particular color will

depend on the terminal they are shown in.

A small collection of semantic faces are also defined, for common uses. For

shadowed text (i.e. dim but there) there is the shadow face. To indicate a

selected region, there is the region face. Similarly for emphasis and

highlighting the emphasis and highlight faces are defined. There is also

code for code-like text, key for keybindings, and link for links. For

visually indicating the severity of messages, the error, warning (with the

alias: warn), success, info, note, and tip faces are defined.

These faces can be easily retrieved using the [face""](@ref @face_str) macro.

For instance, face"blue" returns the Face that defines the colour blue, and

face"emphasis" returns the Face defined for marking emphasised text.

face"default"

face"highlight"

face"tip"

!!! compat “Julia 1.14”

The face"" macro and current face naming system was introduced with Julia 1.14.

In Julia 1.11 through to 1.13 (and the backwards compatibility package registered in General)

faces are named with Symbols, and a global faces dictionary is used. The old API is still

supported for backwards compatibility, but it is strongly recommended to support the new

system by putting palette definitions behind a version gate if compatibility with older library

versions is required.

[Palettes](@id stdlib-styledstrings-face-palettes)

While the base faces provided are often enough for basic styling, they convey

little semantic meaning. Instead of a package say using face"bold" or an

anonymous Face for table headers it would be more appropriate to create a

named face for each distinct purpose. This benefits three sets of people:

- Package authors: as it’s much easier to implement readable code and consistent styling by naming the styles you use

- The ecosystem: as it allows for style reuse across packages

- End users: as named faces allow for customisation (more on that later)

!!! tip “Effective use of named faces”

It is strongly recommended that packages should take care to use and introduce

semantic faces (like code and table_header) over direct colors and styles (like cyan).

Sets of named faces are created with the @defpalette! macro. Simply

wrap a series of <name> = Face(...) statements in a begin ... end block and

declare all the faces you want to create. For example:

@defpalette! begin

table_header = Face(weight = :bold, underline = true)

table_row_even = Face(background = bright_black)

table_row_odd = Face(background = black)

table_separator = Face(foreground = yellow)

end

All faces defined by @defpalette! are recognised by [face""](@ref

@face_str). In our table example, this means that face"table_header" will work

just as face"cyan" does.

To support face customisation, along with other runtime features, it is

necessary that whenever @defpalette! is used a call to @registerpalette! is

put in the module’s __init__ function.

function __init__()

@registerpalette!

end

The ability to use a face defined within a module, like face"table_header", is

specific to that module. Should face"table_header" be put in another module,

it will not be found. In order to use faces defined in another module or

package, we can invoke @usepalettes!. This imports the faces defined

by the modules provided as arguments.

@usepalettes! MyColors

face"burgundy" # defined in MyColors

!!! note “Declare and import faces before using them”

Face resolution with face"" is performed at macro-expansion (compile) time.

A consequence of this is that faces must be defined and imported with @defpalette!

and @usepalettes! before any face"" calls referencing those faces.

It is also possible to specify a color provided by another module using a

qualified name, of the form face"<module path>.<name>. In our example,

face"MyColors.burgundy" could be used if @usepalettes! wasn’t called.

[Dynamic face theming](@id stdlib-styledstrings-theming)

When trying to create well-designed content for the terminal, only being able to assume 8 colors with two shades, but not knowing what those colors are, can be frustratingly limiting. However, reaching outside the 16 shades is fraught. Take picking a highlight colour. For any single color you pick, there’s a user with a terminal theme that makes the resulting content unreadable.

By hooking into REPL initialisation, StyledStrings is able to query the terminal state and determine what the actual colors used by the terminal are. This allows for simplistic light/dark detection, as well as more sophisticated color blending.

Light and dark variants of a face can be embedded in the @usepalettes! call that defines the faces, by using .light and .dark suffixes. For example:

@defpalette! begin

table_highlight = Face(background = 0xc2990b) # A muddy yellow. Not great but often legible

table_highlight.light = Face(background = 0xffda90) # A pale yellow for light themes

table_highlight.dark = Face(background = 0x876804) # A dull yellow for dark themes

end

Users can customise the light and dark face variants, even if no variants are

declared in @defpalette!. At runtime, the light and dark variants will

automatically be applied when a light/dark terminal theme is detected.

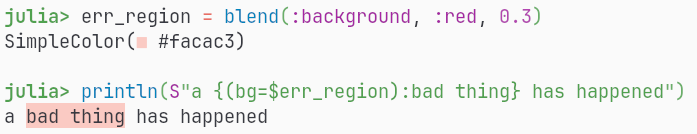

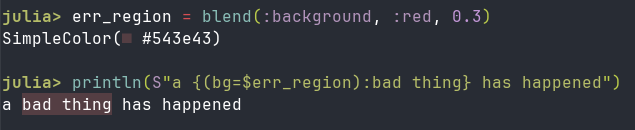

This helps us avoid the worst case of illegible content, but we can still do better. People are still using odd themes which make it hard to pick shades and hues that are completely reliable, and it’s easy to clash with the colour hues already used in the terminal color theme (for example, if the particular green you pick clashes). To produce the best experience, we can blend the colors already used in the terminal theme to produce the best hue and shade. This is done with three key functions:

recolor as a hook for when theme information has been collected/updatedblend for blending colorssetface! for updating the face style

Using these tools, we can set table_highlight to fit in seamlessly with the existing terminal theme.

# Must be placed within `__init__`

StyledStrings.recolor() do

faintyellow = StyledStrings.blend(face"yellow", face"background", 0.7)

StyledStrings.setface!(face"table_highlight", Face(background = faintyellow))

end

Whether the extra capability afforded by this approach will vary face-by-face. It is most valuable when reaching for colors in-between those offered by the terminal, or based on the particular foreground/background shades or hues.

Applying faces to a AnnotatedString

By convention, the :face attributes of a [AnnotatedString](@ref

Base.AnnotatedString) hold information on the [Face](@ref StyledStrings.Face)s

that currently apply.

!!! compat “Julia 1.14”

Faces used to be given by either a single Face, a Symbol naming a face, or a vector

of Faces/Symbols. As of version 1.14 this is deprecated and only supported for

backwards compatibility. This should not be used in any new code.

The show(::IO, ::MIME"text/plain", ::AnnotatedString) and show(::IO, ::MIME"text/html", ::AnnotatedString) methods both look at the :face attributes

and merge them all together when determining the overall styling.

We can supply :face attributes to a AnnotatedString during construction, add

them to the properties list afterwards, or use the convenient [Styled String

literals](@ref stdlib-styledstring-literals).

str1 = AnnotatedString("blue text", [(1:9, :face, face"blue")])

str2 = styled"{blue:blue text}"

str1 == str2

sprint(print, str1, context = :color => true)

sprint(show, MIME("text/html"), str1, context = :color => true)

[Styled String Literals](@id stdlib-styledstring-literals)

To ease construction of [AnnotatedString](@ref Base.AnnotatedString)s with [Face](@ref StyledStrings.Face)s applied,

the [styled"..."](@ref @styled_str) styled string literal allows for the content and

attributes to be easily expressed together via a custom grammar.

Within a [styled"..."](@ref @styled_str) literal, curly braces are considered

special characters and must be escaped in normal usage (\{, \}). This allows

them to be used to express annotations with (nestable) {annotations...:text}

constructs.

The annotations... component is a comma-separated list of three types of annotations.

- Face names (resolved using the same process described for

face"")

- Inline

Face expressions (key=val,...)

key=value pairs

Interpolation is possible everywhere except for inline face keys.

For more information on the grammar, see the extended help of the

[styled"..."](@ref @styled_str) docstring.

As an example, we can demonstrate the list of built-in faces mentioned above like so:

julia> println(styled"

The basic font-style attributes are {bold:bold}, {light:light}, {italic:italic},

{underline:underline}, and {strikethrough:strikethrough}.

In terms of color, we have named faces for the 16 standard terminal colors:

{black:■} {red:■} {green:■} {yellow:■} {blue:■} {magenta:■} {cyan:■} {white:■}

{bright_black:■} {bright_red:■} {bright_green:■} {bright_yellow:■} {bright_blue:■} {bright_magenta:■} {bright_cyan:■} {bright_white:■}

Since {code:bright_black} is effectively grey, we define two aliases for it:

{code:grey} and {code:gray} to allow for regional spelling differences.

To flip the foreground and background colors of some text, you can use the

{code:inverse} face, for example: {magenta:some {inverse:inverse} text}.

The intent-based basic faces are {shadow:shadow} (for dim but visible text),

{region:region} for selections, {emphasis:emphasis}, and {highlight:highlight}.

As above, {code:code} is used for code-like text.

Lastly, we have the 'message severity' faces: {error:error}, {warning:warning},

{success:success}, {info:info}, {note:note}, and {tip:tip}.

Remember that all these faces (and any user or package-defined ones) can

arbitrarily nest and overlap, {region,tip:like {bold,italic:so}}.")

Documenter doesn't properly represent all the styling above, so I've converted it manually to HTML and LaTeX.

<pre>

The basic font-style attributes are <span style="font-weight: 700;">bold</span>, <span style="font-weight: 300;">light</span>, <span style="font-style: italic;">italic</span>,

<span style="text-decoration: underline;">underline</span>, and <span style="text-decoration: line-through">strikethrough</span>.

In terms of color, we have named faces for the 16 standard terminal colors:

<span style="color: #1c1a23;">■</span> <span style="color: #a51c2c;">■</span> <span style="color: #25a268;">■</span> <span style="color: #e5a509;">■</span> <span style="color: #195eb3;">■</span> <span style="color: #803d9b;">■</span> <span style="color: #0097a7;">■</span> <span style="color: #dddcd9;">■</span>

<span style="color: #76757a;">■</span> <span style="color: #ed333b;">■</span> <span style="color: #33d079;">■</span> <span style="color: #f6d22c;">■</span> <span style="color: #3583e4;">■</span> <span style="color: #bf60ca;">■</span> <span style="color: #26c6da;">■</span> <span style="color: #f6f5f4;">■</span>

Since <span style="color: #0097a7;">bright_black</span> is effectively grey, we define two aliases for it:

<span style="color: #0097a7;">grey</span> and <span style="color: #0097a7;">gray</span> to allow for regional spelling differences.

To flip the foreground and background colors of some text, you can use the

<span style="color: #0097a7;">inverse</span> face, for example: <span style="color: #803d9b;">some </span><span style="background-color: #803d9b;">inverse</span><span style="color: #803d9b;"> text</span>.

The intent-based basic faces are <span style="color: #76757a;">shadow</span> (for dim but visible text),

<span style="background-color: #3a3a3a;">region</span> for selections, <span style="color: #195eb3;">emphasis</span>, and <span style="background-color: #195eb3;">highlight</span>.

As above, <span style="color: #0097a7;">code</span> is used for code-like text.

Lastly, we have the 'message severity' faces: <span style="color: #ed333b;">error</span>, <span style="color: #e5a509;">warning</span>,

<span style="color: #25a268;">success</span>, <span style="color: #26c6da;">info</span>, <span style="color: #76757a;">note</span>, and <span style="color: #33d079;">tip</span>.

Remember that all these faces (and any user or package-defined ones) can

arbitrarily nest and overlap, <span style="color: #33d079;background-color: #3a3a3a;">like <span style="font-weight: 700;font-style: italic;">so</span></span>.</pre>

\begingroup

\ttfamily

\setlength{\parindent}{0pt}

\setlength{\parskip}{\baselineskip}

The basic font-style attributes are {\fontseries{b}\selectfont bold}, {\fontseries{l}\selectfont light}, {\fontshape{it}\selectfont italic},\\

\underline{underline}, and {strikethrough}.

In terms of color, we have named faces for the 16 standard terminal colors:\\

{\color[HTML]{1c1a23}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{a51c2c}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{25a268}\(\blacksquare\)}

{\color[HTML]{e5a509}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{195eb3}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{803d9b}\(\blacksquare\)}

{\color[HTML]{0097a7}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{dddcd9}\(\blacksquare\)} \\

{\color[HTML]{76757a}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{ed333b}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{33d079}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{f6d22c}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{3583e4}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{bf60ca}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{26c6da}\(\blacksquare\)} {\color[HTML]{f6f5f4}\(\blacksquare\)}

Since {\color[HTML]{0097a7}bright\_black} is effectively grey, we define two aliases for it:\\

{\color[HTML]{0097a7}grey} and {\color[HTML]{0097a7}gray} to allow for regional spelling differences.

To flip the foreground and background colors of some text, you can use the\\

{\color[HTML]{0097a7}inverse} face, for example: {\color[HTML]{803d9b}some \colorbox[HTML]{803d9b}{\color[HTML]{000000}inverse} text}.

The intent-based basic faces are {\color[HTML]{76757a}shadow} (for dim but visible text),\\

\colorbox[HTML]{3a3a3a}{region} for selections, {\color[HTML]{195eb3}emphasis}, and \colorbox[HTML]{195eb3}{highlight}.\\

As above, {\color[HTML]{0097a7}code} is used for code-like text.

Lastly, we have the 'message severity' faces: {\color[HTML]{ed333b}error}, {\color[HTML]{e5a509}warning},\\

{\color[HTML]{25a268}success}, {\color[HTML]{26c6da}info}, {\color[HTML]{76757a}note}, and {\color[HTML]{33d079}tip}.

Remember that all these faces (and any user or package-defined ones) can\\

arbitrarily nest and overlap, \colorbox[HTML]{3a3a3a}{\color[HTML]{33d079}like

{\fontseries{b}\fontshape{it}\selectfont so}}.

\endgroup

[Customisation](@id stdlib-styledstrings-customisation)

[Face configuration files (Faces.toml)](@id stdlib-styledstrings-face-toml)

It is good for the name faces in the global face dictionary to be customizable.

Theming and aesthetics are nice, and it is important for accessibility reasons

too. A TOML file can be parsed into a list of [Face](@ref StyledStrings.Face) specifications that

are merged with the pre-existing entry in the face dictionary.

A [Face](@ref StyledStrings.Face) is represented in TOML like so:

[facename]

attribute = "value"

...

[package.facename]

attribute = "value"

For example, if the shadow face is too hard to read it can be made brighter

like so:

[shadow]

foreground = "white"

Should the package MyTables define a table_header face, you could change its

colour in the same manner:

[MyTables]

table_header.foreground = "blue"

Light and dark face variants may be set under the top-level tables [light] and [dark]. For instance, to set the table header to magenta in light mode, one may use:

[light.MyTables]

table_header.foreground = "magenta"

On initialization, the config/faces.toml file under the first Julia depot (usually ~/.julia) is loaded.

Face remapping

One package may construct a styled string without any knowledge of how it is intended to be used. Should you find yourself wanting to substitute particular faces applied by a method, you can wrap the method in remapfaces to substitute the faces applied during construction.

StyledStrings.remapfaces(face"warning" => face"error") do

styled"you should be {warning:very concerned}"

end

This changes the annotations in the styled strings produced within the remapfaces call.

Display-time face rebinding

While remapfaces is applied during styled string construction, it is also possible to change the meaning of each face while they are printed. This is done via withfaces.

withfaces(face"yellow" => face"red", face"green" => face"blue") do

println(styled"{yellow:red} and {green:blue} mixed make {magenta:purple}")

end

This is best applied when you want to temporarily change how faces appear,

without modifying the underlying string data.

[API reference](@id stdlib-styledstrings-api)

Styling and Faces

StyledStrings.@styled_str

StyledStrings.styled

StyledStrings.@face_str

StyledStrings.@defpalette!

StyledStrings.@registerpalette!

StyledStrings.@usepalettes!

StyledStrings.Face

StyledStrings.remapfaces

StyledStrings.withfaces

StyledStrings.SimpleColor

StyledStrings.parse(::Type{StyledStrings.SimpleColor}, ::String)

StyledStrings.tryparse(::Type{StyledStrings.SimpleColor}, ::String)

StyledStrings.merge(::StyledStrings.Face, ::StyledStrings.Face)

StyledStrings.recolor

StyledStrings.blend

StyledStrings.setface!

Deprecated API

StyledStrings.addface!

![]() .

.![]() I’m very happy to clarify details, and go into depth on aspects of the design (e.g. topologically sorting face dependencies within a palette to allow for order-independent definition).

I’m very happy to clarify details, and go into depth on aspects of the design (e.g. topologically sorting face dependencies within a palette to allow for order-independent definition).